We just did something crazy: we completely rewrote our backend from Python to Node just one week after our launch.

We did this so we can scale. Yes, scale. A week in.

In some ways, it's a good time right? The codebase is still small and we don't have too many users.

But on the other hand, it goes completely against the advice given to early-stage startups which is to just ship and sell, and worry about scale once you've hit product-market-fit. "Do things that don't scale", as PG put it.

You see, we didn't have a magical launch week that flooded us with users and force us to scale. And generally you can expect that any stack you pick should be able to scale reasonably well for a long time until you actually get to the point where you should consider changing frameworks or rewriting your backend in a different language (read: Rust).

So why do it?

Python async sucks

I'm a big fan of Django. I was introduced to it at PostHog and it's become my go-to backend for most projects since. It gets you off the ground really fast, has great tooling and abstractions, and is still flexible enough to tweak to your needs.

So naturally, when I started writing our backend at Skald, I started us off with Django too.

Now, we make a lot of calls to LLM and embedding APIs at Skald, so we're generally doing a lot of network I/O that we'd like to be async. Not only that, we often want to fire a lot of requests concurrently, such as when need to generate vector embeddings for the various chunks of a document.

And things quickly got really messy in Django.

I'll preface this by saying that neither of us has a lot of experience writing Python async code (I've mostly worked on async-heavy services in Node) but I think this is partly the point here: it's really hard and unintuitive to write solid and performant Python async code. You need to go deep into the foundations of everything in order to be able to do so.

I'm actually really interested in spending proper time in becoming more knowledgeable with Python async, but in our context you a) lose precious time that you need to use to ship as an early-stage startup and b) can shoot yourself in the foot very easily in the process.

Nevertheless, I thought I was to blame. "Bad programmer! Bad programmer!" was what I was hearing in my head as I tried to grasp everything. But while more knowledgeable folks would certainly have a better time, we discovered that the foundations of Python async are actually a bit shaky too.

Unlike JavaScript, which had the event loop from the beginning, and Go, that created the concept of goroutines (both concurrency models that I quite like and have used in production), Python async support was patched on later, and that's where the difficulty lies.

Two blog posts that cover this really well are "Python has had async for 10 years -- why isn't it more popular?" and "Python concurrency: gevent had it right", both conveniently published not long before I started digging into all this.

As for us, we learned a few things:

- Python doesn't have native async file I/O.

- Django still doesn't have full async support. Async in the ORM is not done yet and the colored functions problem really shines here. You can technically use Django with async, but their docs on this have so many caveats that it should scare anyone.

- You gotta write

sync_to_asyncandasync_to_synceverywhere. - All sorts of models have emerged to bring better async support to different parts of the Python ecosystem, but as they're not native they have their own caveats. For instance, aiofiles brings async API-compatible file operations but uses a thread pool under the hood, and Gevent with its greenlets is pretty cool but it literally patches the stdlib in order to work.

- Due to a lot of async support in Python relying on layers that sit on top of the language rather than being native, you need to be careful about the async code you write as it will have different implications depending on e.g. the Gunicorn worker type you run (good luck learning much about those from the Gunicorn docs, btw).

Overall, just getting an equivalent of Promise.all to work, while understanding all of its gotchas was not simple at all.

Faced with this, I went into the PostHog codebase.

I worked at PostHog for three years and we had no async in the Django codebase back then but they're a massive company and they have AI features now so they must have figured this out!

And what I realized was that they're still running WSGI (not ASGI) with Gunicorn Gthread workers (where the max concurrent requests you're able to handle is usually max 4x CPU cores), thus not getting much benefit from running things async. The codebase also has a lot of utils to make async work properly, like their own implementation of async_to_sync. So I guess way they're handling a lot of load is probably just horizontal scaling.

There's simply no great way to run async in Django.

Ok, now what?

We essentially concluded that Django was going to hurt us really soon, not just when we started to have a lot of load.

Without too many users we'd already need to start running multiple machines in order to not have terrible latency, plus we'd be writing clunky code that would be hard to maintain.

We could of course just "do things that don't scale" for now and just solve the problem with money (or AWS credits), but it didn't feel right. And being so early would make the migration to another framework much easier.

At this point, some people are probably screaming at their screens going: "just use FastAPI!" -- and we did indeed consider it.

FastAPI does have proper async support and is quite a loved framework said to be performant. And if you want an ORM with it you could use SQLAlchemy which also supports async.

Migrating to FastAPI would have probably saved us a day or two (our migration took 3 days) due to being able to reuse a lot of code without translating it, but at this point we weren't feeling great about the Python async ecosystem overall, and we had actually already written our background worker service in Node, so we thought it would be a good opportunity to go all-in on one ecosystem.

And so migrate to Node we did. We took a little time picking the framework + ORM combo but settled on Express + MikroORM.

Yeah sure Express is old but it's battle-tested and feels familiar. Coming over to the JS event loop was the main point of all this anyway.

What we gained, what we lost

Gained: Efficiency

Our initial benchmarks show we've gained ~3x throughput out of the box and that's just with us running what is mostly sequential code in an async context. Being over on Node now, we're planning on doing a lot concurrent processing when chunking, embedding, reranking, and so on. This means this change should have an even greater payoff over time.

Lost: Django

Losing Django hurts, and we've already found ourselves building a lot more middleware and utilities ourselves on the Express side. Adonis exists, which is a more fully-featured Node framework, but moving to a whole new ecosystem felt like more work to us than just using something minimal.

What I'm missing the most is the ORM, which in my opinion is really ergonomic. And while you always have to be careful with ORMs when looking to extract the best possible performance, the Django ORM does do some nice things under the hood in order to make it performant enough to write queries in Python, and I learned a bit more about this when migrating our Django models over to MikroORM entities.

Gained: MikroORM

MikroORM was a consolation prize in this whole migration. I still much prefer the Django ORM but at the same time different ecosystems call for different tooling.

I'd never used it before and was positively surprised to find Django-like lazy loading, a migrations setup that felt much better than Prisma's, as well as a reasonably ergonomic API (once you manually set up the foundations right).

Overall, we're early into this change, but currently happy to have picked MikroORM over the incumbent Prisma.

Lost: The Python ecosystem

I think this is pretty self-explanatory. While most tools for building RAGs and agents have Python and TypeScript SDKs, Python still takes priority, and we're just talking about API wrappers here.

Once you want to actually get into ML stuff yourself, there's just no competition. I suspect that as we get more sophisticated we'll end up having a Python service, but for now we're ok.

Gained: Unified codebase

We'd always realized that migrating to Node would mean we'd have two Node services instead of a Python one and a Node one, but it didn't occur to us until a day in that we could actually merge the codebases and that that would be extremely helpful.

There was a lot of duplicate logic across the Node worker and the Django server, and now we've unified the Express server and background worker into one codebase, which feels so much better. They can both use the ORM now (previously the worker was running raw SQL) and share a bunch of utils.

Gained: Much better testing

This is not a pytest vs jest thing, it's just that in order to make sure everything was working as expected after migrating, we just wrote a ton more tests. This and some refactoring were welcome side benefits.

How we did it

I think it's about time to wrap this post up, but here are some quick notes about the actual migration process.

- It took us three days.

- We barely used AI code generation at all until the final bits -- it felt important to us to understand the foundations of our new setup really well, particularly the inner workings of the new ORM. Once we had the foundations of everything down Claude Code was quite helpful in generating code for some less important endpoints, and also helped us in scanning the codebase for issues.

- We almost quit multiple times. We were getting customer requests for new features and had some bugs in the Django code and it felt like we were wasting time migrating instead of serving customers.

Would we do it again?

Honestly, we're quite happy with our decision and would 100% do it again. Not only will this pay off in the long term but it's already paying off today.

We learned a lot of stuff in the process too, and if the whole point of this whole post is that someone comes to tell me that we're dumb and we should just have done X or Y, or comes to teach me about how Python async works, then that will honestly be great. For my part, I gladly recognize my inexperience with Python async and if I can learn more about it, that's a win.

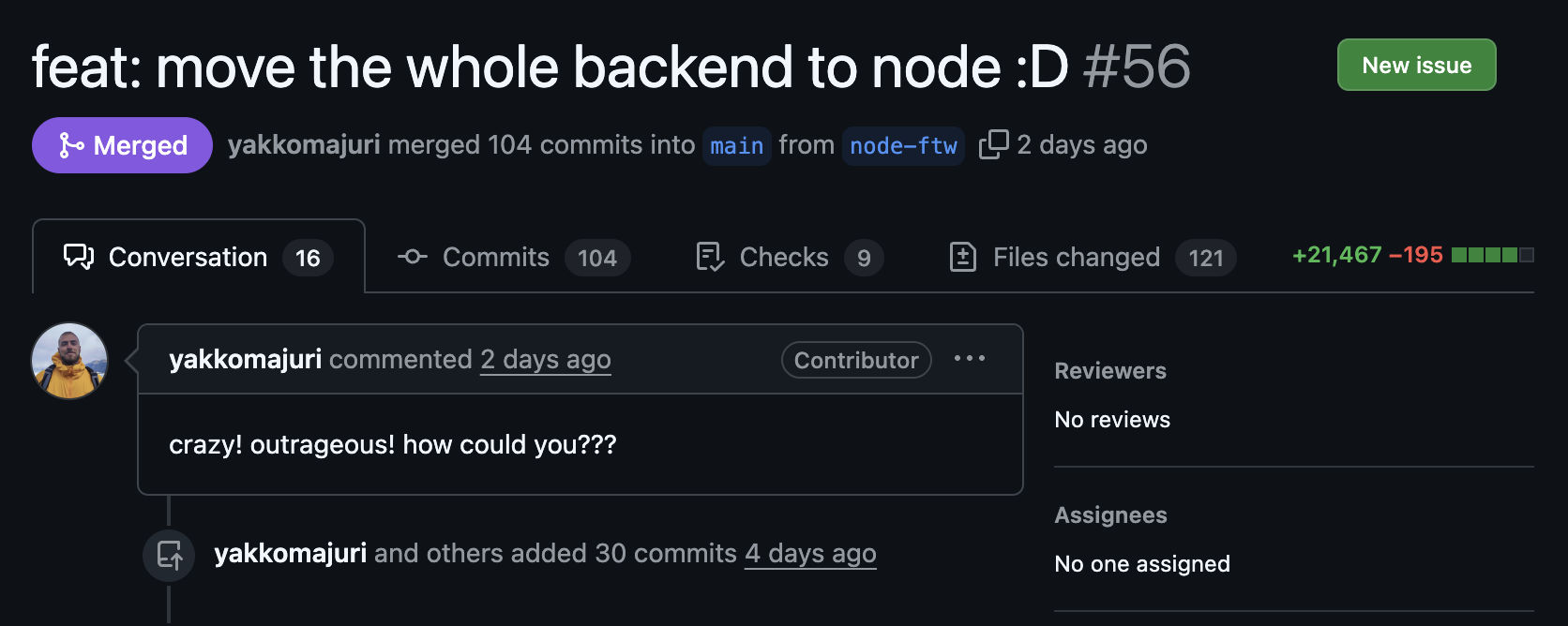

And if you're interested in actually seeing the code, check out the following PRs:

Skald is an MIT-licensed RAG API platform, so if you have any thoughts or concerns, you can come yell at us on GitHub, or open a PR to rewrite the backend to your framework of choice :D